Guest blog post – Professor Mike Stephenson’s Lecture

On Monday 1th January, Professor Mike Stephenson gave a lecture on Shale Gas: Fracking, Groundwater and Earthquakes at Lancaster University. One of Refracktion’s supporters was able to get a ticket and this is their report on the lecture.

The talk was organised by the Lancaster University Environment Centre and Royal Geographical Society North West region, and held in the Biology Lecture Hall, complete with skeleton of dinosaur suspended from the ceiling.

Professor Stephenson is Head of Science (Energy) at the British Geological Society (BGS) and Director of the Nottingham Centre for Carbon Capture and Storage. He runs the Energy Programme at BGS which includes Carbon Capture and Storage, Hydrocarbons, Renewables and Unconventional Energy.

I was lucky to get tickets at the last moment and very pleased to be able to go. The lecture theatre was almost full, most of audience were older people, so I guess members of Geog Soc NW, though there were a few people there who were probably students.

Professor Stephenson explained how shale is formed and how it comes to contain methane.

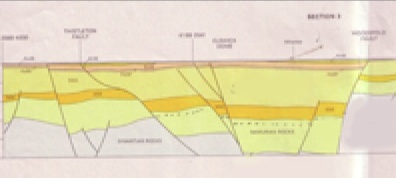

Millions of years ago dead plants, pollen, spores etc. from the land were washed into the sea by rivers, and mixed with algae living in the sea. The plants and algae collected in the mud, so the mud became charged with organic matter. As the mud was buried deeper and deeper over millions of years, the organic matter was ‘cooked up’ and formed methane. The shale under the Fylde is about 2 km down and about 30 million years old. It is a very common rock and is found much closer to the surface in the Bowland Fells. Our shale is Namurian (Millstone Grit Group) which has outcrops in the Pennines and slopes away on both sides of the Pennines, carrying on out to sea, so is deeper in the Irish sea than here in the Fylde.

He then went on to explain the terms Conventional Gas and Unconventional Gas, as they are found in different types of rock and in different rock structures.

Sandstone is a jumble of different sized rounded grains (rather like a box of oranges) with quite large spaces between the grains which hold the oil or gas, and it can move freely through the rock. In a geological structure where the bed of sandstone is folded into an ‘A’ shape and there is an impermeable rock above the sandstone, the oil or gas tends to move up through the sandstone and collects at the top of this ‘A’ shape. A well sunk into this is known as a “conventional” well, and the oil/gas is easily extracted.

Shale rock, however, has flat grains, packed closely together, rather like layers of tightly packed half-penny pieces. There aren’t any large gaps for the gas to collect in or use to move through the rock and so the oil/gas is dispersed throughout the shale bed rather than accumulating at the top. A well sunk into a bed of shale would not get much out and this oil/gas is called “unconventional” as ‘the business has not known how to get the oil/gas out’.

Hydraulic fracturing is the technique used for extraction of Unconventional Gas. The shale is cracked using water or nitrogen, at enormously high pressures ( 350 to 700 atmospheres). This enables the gas to move into the cracks, and so into the well and is then sucked out. So it’s a very different process to a conventional well.

Prof Stephenson then defined the terms Reserve and Resource.

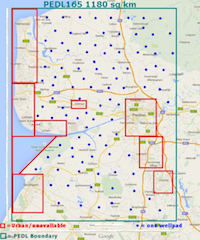

The BGS are currently doing a Resource estimate – i.e. estimating “How much shale gas is in the ground?” and DECC are expected to publish the results in the next 2 weeks, whereas the Reserve estimate is how much shale gas can be got out. Generally the Reserve is approx 10% Resource.

He then told us about an Energy app which sounded quite addictive. It lists where the UK electrical energy comes from – so in the previous 5 mins of the lecture, 14.4% was from coal, 1.9 % was Dutch, 0.7 % French, 4.8% from wind 31% turbines and 17% nuclear…and the UK was generating 50 gigawatts of power. This app is called “UK Energy” and costs £0.69. There is another app UK Energy Watch which appears very similar but is free. Both are availble from Apples’ app store.

The UK is moving to coal as the source of its electricity and coal became the dominant source in April 2012, whereas the US is switching to gas, as it is cheaper to burn shale gas than coal, and is exporting its coal to the UK. Professor Stephenson commented that the US, which is not overly concerned about climate change, is becoming ‘greener’, while the UK, which is concerned about climate change, and has stringent regulations, is becoming less green, because it is using more coal.

[editor – we feel we should point out here that the suggestion that shale gas is greener than coal has been questioned a lot recently (as here) so we are surprised to read that Professor Stephenson reported this as fact, especially given his frequent negative public comments about people who damage the debate by exaggerating things!]

Professor Stephenson showed maps which demonstrated the change, from the Middle East being the centre of oil for the world, to countries all round the world, such as China and Argentina, having their own energy sources, with shale gas present to varying degrees in their energy mix.

He also showed a graph which demonstrated how shale gas has taken off in US since 2009 with projections to the future, showing it becoming a very large part of their energy mix.

Then he discussed some of Poland’s issues with shale gas. Apparently Poland are dependent on coal and largely use their own local Silesian coal, this generates 90% of their electricity needs, and they get their gas from Russia. It would be difficult for them to switch to shale gas but the Polish government t is keen on shale gas, Poland has a lot of shale and shale gas would enable them to drastically cut their emissions, and also to become independent of Russia.

He mentioned this AEA report http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/eccp/docs/120815_final_report_en.pdf

A lot of licences for shale gas extraction have been issued in Poland but some companies have already left. Apparently it requires a huge amount of energy to create pressures of 600 atmospheres, so there is a big carbon footprint just to get the gas out of the ground.

He went on to explain the difference between thermogenic and biogenic gas, that might be found in water wells.

Thermogenic is very old, it is the gas that has been formed from plants and algae, buried and heated and originates in shale, whereas biogenic gas is much younger, and the two types of methane can be told apart by the ratios of Carbon12 to Carbon13

So far so good, an excellent introduction, but at this point it became a tad more complicated. Prof Stephenson did at one point display a graph and apologise, saying it was the only one…it wasn’t!

The next part of the lecture was to discuss the possibility of groundwater being contaminated by methane from fracking, and Prof Stephenson discussed 3 academic papers that had investigated this.

The first paper by Osborn et al,

http://www.nicholas.duke.edu/hydrofracking/Osborn%20et%20al%20%20Hydrofracking%202011.pdf found higher methane concentrations in water wells near to shale gas wells and the Delta13 carbon figure suggested it was thermogenic, and so thought to be methane that had got into the groundwater because of the nearby fracking. However there was no evidence of fracking fluids there, which was a puzzle. This paper which had been peer reviewed, has been queried and lost some credibility because they hadn’t measured the methane levels before the fracking.

Next came a paper by Molofsky et al http://www.cabotog.com/pdfs/MethaneUnrelatedtoFracturing.pdf who work for an oil company and the paper has not been peer-reviewed. This found higher levels of methane along water courses and used the Osborn data but found that the methane is of a different type than that from the fracked shale, so has come to the surface but not from the fracked rock, in that area.

And the 3rd paper is on Hydraulic connectivity and written by Osborn’s colleagues at Duke University.

(Possibly this paper ? http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2012/07/03/1121181109.full.pdf )

It examines water chemistry to establish that water from the Marcellus shales has risen into groundwater and water wells, somehow/somewhen over 400 million years.

Well I did say the lecture got a bit technical!

Professor Stephenson then mentioned that the BGS were doing baseline studies of methane in water before any activity (n.b. to Readers: Cuadrilla have already been active for 2 years here.)

He discussed the earthquakes that resulted from the fracking at Preese Hall in 2011, that they were less than magnitude 3 which is one you would ‘feel’ and that the BGS had detected them. He showed us wave forms for the two larger tremors at the time, (Mag 2.3 on 1st April 2011 and Mag. 1.5 on 27 May 2011 ) and how they matched and could be directly linked to the time of maximum pressure of the fracking stages.

He concluded the lecture by describing the role of science as an Independent Method to Assess Risk – Low Risk are things we don’t have to worry about and High Risk are things that we need to regulate for public safety and public opinion. eg ‘ Drill properly and seal properly’

And his final slide showed the following conclusions:-

– shale gas is big in the US

– it has already affected energy worldwide

– no evidence of methane contamination from fracking

– tremors very small and new rules are being brought in

– independent science has important role in building regulations and investor and public confidence.

The person beside me commented that ‘no evidence of methane contamination from fracking ‘ just means no evidence, it does not mean that there is no contamination. And the research is ongoing.

The talk was about 1 hour long and followed by 30 minutes of questions, which covered a wide range: comparison of our shale to Barnett shale, radioactivity worries, well integrity, length of time fracking had been done, subsidence, funding of the BGS…

Although the 30 mins for questions was not long enough, the audience were not anxiously waving arms around to get their questions presented, so I rather suspect that the topic was new to most.

Interesting things emerged from the Q+A session, including some that I found more debatable than those in his lecture.

e.g. He said that fracking had been around for 40 years.

While that may be true I felt it misleading to give that answer, as fracking for shale gas in clustered pads using horizontal wells has definitely not been around for 40 years, it’s new technology ( Prof Ingraffea Cornell University.)

He said that a conventional Lancs field had already been fracked and it was interesting to learn that radon can collect and concentrate in gas pipes and needs to be scraped out by machine and disposed of in a special way.

I had understood that the lecture would cover resource size and impacts of extraction – it didn’t really do either of those aspects, resource size clearly being a closely guarded secret and impacts of extraction really should also have included traffic, chemicals, the industrialisation of the sites, high volumes of water use etc

Overall I am glad I went, it was very interesting and I learned a lot from the lecture.

The professor was an excellent lecturer, engaging with the audience, making them laugh at the thought of volcanoes occurring here and taking them down the road that shale gas is safe and a good thing…I feel the audience would wake up the next day ‘knowing’ that there were no issues of subsidence, no issues of radiation, no issues of earthquakes, it was a tried and tested technique and wow – it helps us achieve our climate change commitments too – so how could anyone reasonably object?

However the geology of shale gas is just one small part of the shale gas business, the engineering and regulatory aspects have a huge influence on the risks and environmental effects, and that was not made at all clear. I did not feel that the Professor’s lecture was truly balanced, rather that it was slanted to promoting the government’s line.

I am delighted to say, that after the lecture, 2 strangers came over to me and said that the questions I had asked had raised their awareness, and made them question what they had heard in the lecture.

It would seem that our correspondent was not alone in feeling that the good Professor was not 100% convincing as this comment received yesterday, from somebody we had not heard from before, suggests:

“Prof MS is a very smooth operator – we all came away with the same thought. But although he seemed very knowledgeable and reassuring during his lecture, I think the questions from the audience completely exposed him – I don’t think there was a single question that he answered adequately, and that must have been very clear to everyone in the audience.”

When it was put to this correspondent that DECC had told someone we know that “the meeting went very well at Lancaster and people went away completely satisfied with Professor Stephenson’s presentation” they retorted “I’m astounded that anyone might think he answered the questions satisfactorily. On what basis could they say that?”

We weren’t able to attend the meeting due to illness but we have seen Professor Stephenson’s presentations on this subject on the internet. He is a good presenter, but he seems, as my mother would have put it, “a bit pleased with himself”. He does have a habit of claiming to want a reasonable debate at the same times as lampooning anyone who opposes fracking as an excitable ignoramus. We don’t think that is very appropriate given the valid and reasonable concerns that we have.

Based on presentations we have seen, we conclude, based on his patronising and critical comments about concerns raised by fracking’s opponents with no balancing evidence of the flagrant public inaccuracies perpetrated by fracking supporters (e.g. John Hayes and Boris Johnson) that he appears to have adopted a pro-fracking position. He certainly does seem to be on a mission to convince his audiences that fracking is safe. If it were all about geology he might be qualified to do so. Unfortunately perhaps for all of us, it isn’t. The risk is far more about engineering issues, and he simply isn’t qualified to reassure us about those.

So, perhaps next time he fancies an evening grandstanding to the uneducated Professor Stephenson will dare to venture a little closer to the action. I’m sure if he came to Blackpool the reception for his patronising jokes about volcanoes and cracks in roads would be met with rapturous applause. Or perhaps not. But heck, he might even get a surprise when he finds out just how much we really do know.

So Professor Stephenson – Come to Blackpool and explain to us the error of our ways. I’m sure we can guarantee you a full house!

Are you up for it or is your call for a “mature and reasoned debate” intended more for oratorical effect than anything else.

Post script – our correspondent’s account of this lecture can now also be found on http://www.counterbalance.org.uk/latest/lancslec.htm