It is constantly claimed that one of the main benefits of fracking will be the creation of employment in areas which are in decline.

Hugely varying claims have been made for the extent of direct and induced (supply chain) jobs that will be created.

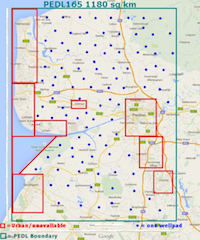

Corin Taylor writing a report to promote fracking for the Institute of Directors famously arrived at a figure of 74,000 , apparently by using a fag packet whilst drinking a cup of coffee. Corin left the IoD to work for Centrica who own a 25% interest in Cuadrilla’s PEDL 165, and then went to work for UKOOG.

Ernst & Young in ‘Getting ready for UK shale gas’ produced for UKOOG (the UK Onshore Operators Group) claimed that up to 64,500 jobs could be needed to develop shale gas reserves in the UK between 2016 and 2032

Perhaps more realistically the Financial Times reported

AMEC predicted at a private meeting at the Decc offices in Whitehall that 15,900 to 24,300 full-time equivalent jobs – direct and indirect – would be created at “peak construction” by the shale gas industry.

The company told people at the event on September 26 that the jobs would typically be short term, at between four and nine years.AMEC also referred to concerns over job leakage, suggesting that at a previous fracking operation at Preese Hall, Lancashire, only 17 per cent of jobs had gone to local people.

‘Potential Economic Impacts of Shale Gas in the Ocean Gateway’ produced by Amion Consulting for IGas and Peel Environmental claimed that fracking in the so-called Ocean Gateway (covering Liverpool, Manchester, Cheshire and Warrington) could create a peak of 3,500 jobs in the area and 15,500 UK-wide.

Regeneris’ ‘Economic Impact of Shale Gas Exploration and Production in Lancashire and the UK’ claimed that Cuadrilla’s production operations in Lancashire could create 1,700 jobs in the county and 5,600 nationwide.

The following chart show the total jobs (direct and induced) guessed at by each report.

We can see from this that there is a massive amount of uncertainty about what fracking could mean in terms of new (FTE equivalent) jobs created. What we do know though is that in DEFRA’s infamously redacted report on the rural impacts of fracking it was reported:

What is less clear is how sustainable the shale gas investments will be in the future and whether rural communities have the right mix of skills to take advantage of the new jobs and wider benefits on offer. Evidence from the USA suggests this is not necessarily the case, with a high proportion of expenditures associated with drilling being made outside of the local rural economy. The majority of local jobs created are therefore likely to be indirect (supply side) jobs that support the sector rather than directly related to the extraction process. These are likely to be small, on a per well basis, and of lower value than the more highly skilled jobs created within the energy industry.

There will also be sectors that gain from the expansion of drilling activity but others that may lose business due to increased congestion or perceptions about the region. These behavioural responses may reduce the number of visitors and tourists to the rural area, with an associated reduction in spend in the local tourism economy. It is recognised that this loss may partially be offset by the rise in new workers and other suppliers entering the area particularly if they rent accommodation or book hotels and use restaurants/hospitality in the area that benefits local rural community business.

so there is clearly the issue is not just how many jobs fracking might create on a temporary basis, but how many jobs it might damage. What is critically important here is the net impact on employment.

Evidence from the USA also shows that the claims made for employment potential by the industry are often massively over-hyped. The 6 state study “Exaggerating Shale Drilling’s Employment Impacts: How & Why” by the Multi-State Shale Research Collaborative tells us

Between 2005 and 2012, less than four new shale-related jobs have been created for each new well. This figure stands in sharp contrast to the claims in some industry-financed studies, which have included estimates as high as 31 for the number of jobs created per well drilled

Perhaps most tellingly, even those who support the industry’s claims make it clear that employment within the industry is a fragile and unreliable experience. Here is how one proponent of the industry described the job security of a driller:

“In the oil and gas industry it is possible to be employed by someone and not be getting any work because you get paid when a well is being drilled, or your employer can be giving you something to keep you going (if they are nice) if it looks like wells are going to be drilled sometime soonish. People can have an employer on their CV for a period and literally not be being paid.” – Dale Green – “BackingFracking” Facebook community 10th September 2015

The jobs may be relatively lucrative (“something near £40k” for a driller we are told by Mr Green, although he didn’t say how near) when you are being paid but is this what local people really need, and will these jobs even be available to many locals?

In addition both the IoD and the Regeneris reports make it very clear that the peak employment will be limited to a period of less than a decade.

So, fracking jobs – insecure, temporary and mostly going to outsiders. What’s not to like?