Any domestic production at all it will self-evidently make some contribution. That much is undeniable.

What is rather less obvious is how fracking could remove our reliance on foreign gas imports – either from pipelined gas from Norway and the USSR or LNG from places like Qatar.

Equally, given that 40 per cent of the UK’s electricity is coming from coal, the question is not whether coal will continue to play a major part in our energy mix over the next half century, but where it will come from and who we will have to rely on for continuity of supply. The low price of coal which is a direct result of the shale gas bubble in the USA has made it more attractive for UK power generation but it has made domestic coal production here in the UK uneconomic, so ironically we are now dependent on coal supplies from Russia, Columbia and the USA to keep the lights on without increasing prices again. Perhaps the headlines should really read “Shale Gas – the last nail in the coffin of the UK’s domestic coal industry”

So, why is the suggestion that fracking will give energy security to the UK so unreliable and misleading? Quite simply because nobody has an real idea how much gas there may be down there!

Cuadrilla’s CEO Fracncis Egan is reported as having claimed that shale could provide 25% of the UK’s demand for gas (although he doesn’t says for how long)

We have spoken of meeting 25% of the UK’s gas demand

It’s a shame he can’t even approach proving that statement isn’t it?

Cuadrilla’s own estimate of the reserve in their licence are is 200 Tcf (Trillion Cubic feet) but we need to bear in mind that only about 10% of that is likely to be recoverable using current technology, so assuming their estimate were accurate that would give a supply of 20 Tcf.

According to Government statistics we use about 3 tcf a year in the UK.

This means that if Cuadrilla’s estimate is a fair one then the Bowland Shale could contain as little as 7 years UK supply in recoverable assets.

Obviously it can’t all be produced at once or it would need to be stored somewhere, but over a period of 25 years, based on a recoverable reserve of 20 TCF and no increase in demand it COULD meet 25% of demand.

Sounds good doesn’t it! You may even be thinking of investing! These journalists think it’s a good bet!

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/money/investing/article-2250251/INVESTORS-Dare-bet-fracking.html

and

But hang on, they don’t seem to have understood the difference between gas in place and gas recoverable though, so maybe you should keep your chequebook in your pocket a little longer 🙂

OK – so it all rests on the reliability of those estimates really doesn’t it?

Let’s lead you in gently then – this from “the Unconventional Hydrocarbon Resources of Britain’s Onshore Basins – Shale Gas” by the British Geological Society in 2011

The UK shale gas industry is in its infancy, and ahead of production testing there are no reliable indicators of potential productivity of its most prospective Jurassic, Carboniferous and Cambrian shale gas plays.

However, by analogy with similar producing shale gas plays in America, the UK shale gas reserve potential could be as large as 150 bcm (5.3 TCF)

ah so about 2 years supply then?

To be fair this was a year ago, and we know the BGS will shortly increase their estimate but if you really want to know how reliable anybody’s estimates are just read this from Energy and Climate Change Committee’s Session 2012-13 The Impact of Shale Gas on Energy Markets

Why are the estimates for shale gas so changeable?

17. Shale gas is a new resource and the production experience to date is relatively limited. This, together with limited geological information and rapidly evolving technology leads to considerable uncertainty over the potential size of the recoverable resource – even in regions where production is relatively advanced. This uncertainty is hidden by the majority of studies which provide point estimates of resource size, rather than a range.

18. Further complications are introduced by the continuing ambiguity over resource definitions, thereby creating the risk of comparing ‘apples and oranges’. As indicated above, the use of different resource definitions will lead to very different resource estimates for the same geological formation. It is not uncommon for different definitions to be compared as though they were equivalent, creating further disagreement and confusion.

19. For most shale gas formations, there is a paucity of reliable geological data. Many of the formations which are thought to contain shale gas have not had extensive analysis through the drilling of wells, the testing of core samples and the assessment of well bore pressures and other variables key to estimating the OGIP and its producible fractions (ERR, TRR, URR, etc.). As first hand geological knowledge of these formations improves the uncertainty surrounding the potentially available resource should begin to reduce.

20. In the absence of new geological data, desk-based studies applying new assumptions to older studies are often produced. This is the most common approach to developing estimates for regions outside North America, but many of those regions continue to lack sufficient geological information. The results are also sensitive to the assumptions used, including the recovery factor. As demonstrated above (), average recovery factors between 15 and 40% are plausible, but this produces global TRR estimates in the range 70 to 180 Tcm. At present there is little evidence to suggest which end of this range is more likely.

21. Once production in a region is underway, more reliable resource estimates may be derived by analysing the production experience to date and extrapolating this experience to undeveloped areas of the same region. As discussed above, a similar approach can be used to estimate resource size in separate but geologically similar regions (analogues). Given the wide variations in productivity within and between shale plays and the difficulty in estimating some geological parameters, the results are very sensitive to the particular analogue that is chosen.

22. Regional resource estimates using this approach are dependent upon the assumed EUR from individual wells. These are typically estimated by statistically fitting a curve to the historical production from a well or group of wells and extrapolating this forward into the future (). These ‘decline curves’ are commonly used to predict the point at which the well will cease production, together with total gas that will be produced over its operating life. When combined with assumptions about average well spacing within the region, this analysis can be used to provide an estimate of the regional TRR. However, the appropriate shape of this ‘production decline curve’ has become a focus of considerable controversy in United States, with several commentators suggesting that the rate of production decline has been underestimated and hence both the longevity of wells and the EUR per well has been overestimated. To the extent that regional resource estimates are based upon EUR estimates for individual wells, this creates the risk that the regional URR will be overestimated as well. Other commentators have contested this interpretation, but the empirical evidence remains equivocal to date owing to the relatively limited production experience.

23. An example of these uncertainties can be seen in the controversy surrounding two recent resource estimates for the Marcellus Shale in the United States. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimate the technically recoverable resources of the Marcellus to be 2.4 Tcm while the consultancy INTEK estimated a much higher figure of 11.6 Tcm. There are three major reasons for this difference. First, the two organisations, subdivided the Marcellus in different ways. Second, the USGS excluded the shale gas in less productive areas of the play, despite this making up 57% of the total INTEK estimate. Third, INTEK assumed that the EUR from wells in the most productive areas would be three times greater than was assumed by the USGS.

24. Overall, given the absence of production experience in most regions of the world, and the number and magnitude of uncertainties that currently exist, estimates of recoverable unconventional gas resources should be treated with considerable caution.

I can’t think of a lengthier way of saying “nobody can possibly know” can you?

Here is how Durham University’s Professor Richard Davies and Nigel Smith of the British Geological Survey (BGS) put it as they gave evidence on shale gas reserves to the Energy and Climate Change Committee.

Cuadrilla Resources’ recent 200tcf resource estimate for the Bowland Shale was discussed in detail during the hearing, especially the likelihood that 10-20% of this amount of gas could be economically recovered. If correct, it could lead to UK shale gas reserves being revised upwards to 20-40tcf.

“My original reserve figure was just a guess as no drilling had taken place in this country,” admitted Smith, referring to BGS’s estimate of 5.3tcf for UK shale gas reserves.2

He told the committee that BGS came up with its reserve estimate for the Bowland Shale in the Pennine Basin (4.7tcf) simply by assuming it had similar production characteristics to the Barnett Shale in the Fort Worth Basin, Texas.

“Cuadrilla by the time it released that figure [200tcf] had drilled two wells. Its figure in my opinion is more reliable than mine,” confirmed Smith.

Davies tried to put UK shale gas resources in context by comparing it with conventional gas production: “The maximum production from North Sea was… just less than 4tcf [annually]… If you make the assumption that you’ve got 10-20% from a 200tcf resource that’s a significant amount.”

“The 200tcf number is very comparable to the resource of the North Sea and the southern North Sea. They’re big numbers,” Davies added. But he thought that even a resource on this scale is unlikely to be globally significant, as US resources are “probably a lot bigger”.

The committee was told that a better estimate of UK reserves depended on greater exploration and on Cuadrilla Resources publishing gas content and well production figures next year.

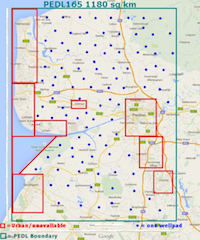

Commenting on Cuadrilla’s licence area and its resource estimate, Smith said: “They’ve got 1,200 square kilometres and they’ve drilled in about 20km2 so it’s still a bit of an exaggeration… to extrapolate it to the rest of the licence area.

Uncertainties over the size of shale gas reserves appear to apply as much to Europe as they do to the UK. Smith described the current shale gas estimate for Europe –2,587tcf resources of which 624tcf is recoverable – as being “based on next to nothing“.”

So if Cuadrilla are right we have a possible contribution to energy security, but everybody seems to agree that nobody has any real idea how much gas there is

…. so can you think of any reasons why Cuadrilla might want to talk up the reserves readers? After all it seems that nobody can check and even Smith from the BGS seem to be basing the potential on what Cuadrilla tells him?