So what did the government NOT want you know about the impacts of fracking?

The Report on The Shale Gas Rural Economy impacts was published in heavily redacted form, generating a storm of protest in March 2014. Over a year later, and coincidentally just after the LCC decisions on Cuadrilla’s two development site applications, on July 1st 2015, the full report was finally published.

So what did they not want us to know?

Well the first thing is the structure of the unredacted report as the table of contents was redacted

Contents

Executive Summary

Section1: Key findings from literature review

Section 2: Areas likely to be effected by Shale Gas licensing

Section 3: Impacts on rural communities from Shale Gas drilling

3.1 Economic Impacts

3.2 Social Impacts

3.3 Environmental ImpactsSection 4: Conclusion

Section 5: Recommendations

Annex: Literature review sources

In the Executive Summary we lost

The analysis in this report has examined the economic, social and environmental impacts associated with shale gas exploration following a rapid literature review.

It seems they didn’t want us to know it was a bit of a hasty affair

Whereas in the UK property rights reside with the state and landowners receive no compensation or reward

So they did not want to highlight the differences between the USA and the UK in terms of people benefiting from Shale development

Overall there will be positive and negative impacts on different groups within rural communities that need to be considered

It seems they only really wanted to present the positives whilst hiding the negatives behind the multiple redactions.

The main high level findings from the report are summarised in the tables below which consider the economic, social and environmental impacts specifically for rural communities rather than the wider economy.

These tables were all redacted too

| ECONOMIC IMPACTS | |||

| Jobs | Services | Energy | Tourism |

| Likely to be positive but uncertain impact as higher skilled jobs may be awarded to workers from outside local area. Although some supply chain businesses may recruit locally boosting rural employment | Positive if council rebates and company contributions are invested in local services and infrastructure. This could be a major benefit for rural communities using these services. | Positive outlook for energy security which will benefit rural communities following increased domestic production rather than relying on foreign imports of gas and vulnerability to political or exchange rate uncertainty. | Broadly neutral. Losses from tourists avoiding area due to shale gas operations may be off-set by increased hospitality to new workers |

We assume that this redaction was because the admission of losses to tourism would be seen as very damaging to the frackers who continually claim that fracking would have a positive impact. Astroturf groups like the North West Energy Task force continually claim that fracking will be good for hoteliers – here we can see that DEFRA can see the reality

| SOCIAL IMPACTS | ||

| Housing impacts | Housing impacts | Services |

| Negative but localised. Additional volume of lorries and vehicles using local rural roads, but depends on location as some may be situated near national highways. | Negative but localised. House prices in close proximity to the drilling operations are likely to fall. However, rents may increase due to additional demand from site workers and supply chain. | Broadly neutral. Depends if new workers at shale gas operations and supply chains create additional demand on schools, doctors and other local rural services that cannot be met by existing services. |

This is one of the bombshells – when profractivists like the Reverend Roberts try to mislead people by claiming that any house price reduction is due to negative publicity resulting from anti-shale protests they are clearly confusing the symptom with the disease, and now we can see that local impacts are admitted to include stress on road networks and services and reductions in house prices. It is clear why they would want to hide those admissions.

| ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS | |||

| Water resources | Noise | Air Quality | Landscape |

| Low impact if properly regulated but risks need to be managed effectively on site. | Localised impact on rural communities living within close proximity of shale gas fracking operations | Low impact If properly regulated but risks need to be managed effectively | Low impact that is site specific, although will have localised impact on businesses reliant on tranquil environment |

Again we can see here admissions of impacts that will be toxic to any attempts to buy a social licence to operate from the fracking industry.

Finally in the executive summary we see they removed

Further work could be undertaken to examine the numbers of communities (residents and businesses) that are likely to be affected from shale gas exploration. However, due to uncertainties on specific license locations at present time we have not undertaken any new research at this stage.

Presumably they don’t want to admit that they don’t really have a lot of evidence to base the Governments cheerleading for shale on.

Moving on to their consideration of the DECC Environmental Impact Assessment for Shale Gas Exploration and Drilling we see that they redacted two sections

| Climate Change | Domestic shale gas production could help to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions associated with imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in particular; however, if LNG or other fossil fuel displaced from the UK is used elsewhere, that could lead to an increase in global GHG emissions. |

| Waste Water | Depending on where wastewater is treated, the additional volume could place a burden on existing wastewater treatment infrastructure capacity, and require further or new investment. However, if on-site treatment and recycling could occur, wastewater volumes could be reduced. |

So we can see that the government tacitly admit that shale gas extraction in the UK is unlikely to lead to any reduction in global CO2 emissions and that they do foresee issues with dealing with the wastewater and are clearly considering allowing re-injection of the flowback fluid. However, it seems they would have preferred us not to know that.

Under “Likely significant effects for Local Communities” they tried to hide

| Other local effects | It is estimated that there will be approximately 14 to 51 vehicle movements to a site each day during exploration and site preparation over a 32 to 145 week period. This could have an adverse impact on traffic congestion, noise or air quality depending on existing roads, traffic and air quality. It could have a more sustained and locally significant effect on communities adjacent to the development sites, or adjacent to the routes to the sites, during exploration and site preparation. |

| Water use | The potential impacts are on water resource availability, aquatic habitats and ecosystems and water quality. Water would typically be sourced from a mains water supply which would need agreement from the relevant water company, or could be abstracted from groundwater or surface water which would need an abstraction licence; in either case, any addition to demand would only be granted where assessed by the regulator as sustainable. Demand could however be substantially reduced if it could be met from recycling and reuse of flow back water. |

Clearly they are concerned about the public’s sensitivity to issues of traffic, air and noise pollution from fracking, and again they would seem to prefer that we were not aware of their consideration of the re-use of flow back water.

And now we come to an odd one. Why would they redact a part of the table looking at the IoD report which deals with environmental benefits?

| Environmental benefits | According to the Committee on Climate Change, if production is well regulated, shale gas can have lower emissions than imported LNG. A recent report for the European Commission also reached the same conclusion. To the extent that UK shale gas supports the production of chemicals and other goods in the UK rather than overseas, emissions will be lower, as UK industry is more energy efficient than in most countries. |

Answers on a post card please!

There is now a large unredacted section until we get to Section 2: Areas likely to be effected (sic) by Shale Gas licensing where we lose

Although licences have been awarded it is unclear which are operational in relation to shale gas exploration and so we have been unable to obtain details of which specific rural locations will be affected at the present time.

It seems again they don’t wish to display the level of what they don’t know here.

However it is in Section 3: Impacts on rural communities from Shale Gas drilling that we see the bulk of the redactions including this bombshell:

What is less clear is how sustainable the shale gas investments will be in the future and whether rural communities have the right mix of skills to take advantage of the new jobs and wider benefits on offer. Evidence from the USA suggests this is not necessarily the case, with a high proportion of expenditures associated with drilling being made outside of the local rural economy. The majority of local jobs created are therefore likely to be indirect (supply side) jobs that support the sector rather than directly related to the extraction process. These are likely to be small, on a per well basis, and of lower value than the more highly skilled jobs created within the energy industry.

There will also be sectors that gain from the expansion of drilling activity but others that may lose business due to increased congestion or perceptions about the region. These behavioural responses may reduce the number of visitors and tourists to the rural area, with an associated reduction in spend in the local tourism economy. It is recognised that this loss may partially be offset by the rise in new workers and other suppliers entering the area particularly if they rent accommodation or book hotels and use restaurants/hospitality in the area that benefits local rural community business.

The longer term economic impacts to rural communities is uncertain and will largely depend upon how revenue raised during the shale gas boom is reinvested within the local economy to create sustainable jobs for the future that do not rely on the shale gas sector.

So here it is admitted that few locals will in fact benefit from well paid jobs which will probably go to experts from outside the area. It sounds as though “These are likely to be small, on a per well basis, and of lower value than the more highly skilled jobs created within the energy industry” is a tacit admission that what we are talking about are a few security guards on each site. It is also admitted that tourism will suffer if shale gas goes into production mode.

Further on we lost another admission that they don’t know what they don’t know

Further work will therefore be needed to monitor and assess the net economic impact of shale gas on rural communities, particularly if as expected this sector expands significantly over the next few years. The table below provides a summary of the key economic variables with an indication of the expected significance of impact.

along with the tables which sum up the conclusions which re-iterate the facts that jobs for locals will be very limited and tourism will be negatively impacted.

Table 1: Summary of economic impact of shale gas on rural communities

| Jobs | Services | Energy | Tourism |

| Likely to be positive but uncertain impact as higher skilled jobs may be awarded to workers from outside local area. Although some supply chain businesses may recruit locally boosting rural employment | Positive if council rebates and company contributions are invested in local services and infrastructure. This could be a major benefit for rural communities using these services. | Positive outlook for energy security which will benefit rural communities following increased domestic production rather than relying on foreign imports of gas and vulnerability to political or exchange rate uncertainty | Broadly neutral.Losses from tourists avoiding area due to shale gas operations may be off-set by increased hospitality to new workers |

The analysis 3.2 Social Impacts loses a large section dealing with road congestion – a factor which played a great part in the determination of the Roseacre Wood application. This makes it very clear that impacts will be over a wide area (at least 5 miles) around each site, with as many as 36,735 vehicle movements per site

-

a) Increased congestion on roads and noise

The nature of the drilling work will involve trucks and other heavy vehicles hauling equipment and transporting staff to and from the operation. This is expected to have a higher impact on those communities living within a 5 mile radius of the site, although road congestion may spread wider but will depend on infrastructure and maintenance levels. These externalities can be managed to a certain extent by the operator being considerate of residents and planning efficient transport usage to minimise disruption.

Results from the literature review shows that the total vehicle movements per well pad are broadly similar. The SEA report breaks down vehicle movements for low and high activity scenarios. 4950-17,600 vehicle movements are assumed for the low activity and 10290-36735 vehicle movements for the high activity. The Ricardo AEA report does not break vehicle figures down according to scenarios. It quotes figures from the USA of 7,000 to 11,000 vehicle movements for a single ten well pad. This figure would be reduced substantially if water and flowback fluid could be transferred by pipeline. The Ricardo AEA report is consistent with the Institute of Directors estimate of 870 truck movements per well.

Calculations on the number of vehicle movements per day differ. The SEA report assumes 16- 51 vehicle movements per day during the production development phase, which covers well construction and hydraulic fracturing. The Ricardo AEA report does not give a daily average figure. It suggests there could be 5000 truck movements for the drilling phase for a ten well pad. The temporal distribution of these activities would be uneven so it suggests the total number of trips during the heaviest period could be as high as 250 per day.

Perhaps the most toxic reaction is this one within the section on Impact on housing demand and property prices

As operations expand and new workers arrive into rural locations there may be a modest increase in demand for accommodation that could raise rents and cause affordability issues for rural residents seeking accommodation. For example, the Cuadrilla research quotes a figure of 83 FTE jobs being created on average for each drilled well in the UK, of which a % may seek accommodation in rural areas. On the other hand, those residents owning property close to the drilling site may suffer from lower resale prices due to the negative perception being located near the facility and potential risks. However, these effects will depend on a range of wider factors that influence rents and house prices such as planning policy, growth and investment from wider sectors, schools, flooding and insurance etc. Evidence from the US experience is listed below.

This section makes it clear that there is a double whammy with those in rented accommodation being squeezed out by the temporary influx of fracking workers, whilst owner occupiers will suffer a blight on their homes. Then there is a second bombshell with the quantification of the blight and the admission that insurance cover will probably be affected.

Overall the evidence on impact on property prices in the literature is quite thin and the results are not conclusive. There could potentially be a range of 0 to 7% reductions in property values within 1 mile of an extraction site to reflect the impacts, where the high range reflects the top end of the Boxall et al (2005) estimate for the price fall.

Properties located within a 1 – 5 mile radius of the fracking operation may also incur an additional cost of insurance to cover losses in case of explosion on the site. Such an event would clearly have social impacts, although the probability is expected to be low if the regulator and company manage these risks effectively.

In fact there are about 146,000 households in Blackpool, Wyre and Fylde who could be affected here. About 75% are owner occupied. 7 % of the owner occupied housing stock at an average price of £150k is about £1.1 billion.

Talking of the stress on local services the report mentions the hypothetical gains to the community but the doubts expresses as to their adequacy was hidden from us

However, it is unclear whether this level of investment will be sufficient to meet the additional demand if new schools or hospitals are needed to ensure service provision for existing rural communities is maintained. The table below provides a summary of the main social impacts on rural communities that are expected from the expansion of shale gas activities

Unsurprisingly perhaps this table was also suppressed as it shows many of the same conclusions as were redacted above

Table 2: Summary of social impact of shale gas on rural communities

| Congestion | Housing impacts | Services |

| Negative but localised.Additional volume of lorries and vehicles using local rural roads, but depends on location as some may be situated near national highways. | Negative but localised.House prices in close proximity to the drilling operations are likely to fall. However, rents may increase due to additional demand from site workers and supply chain | Broadly neutral.Depends if new workers at shale gas operations and supply chains create additional demand on schools, doctors and other local rural services that cannot be met by existing services. |

And now we come to another massive set of redactions covering up the conclusions on Environmental Impacts. The first area redacted is the section dealing with water. Here there is an admission that toxic chemicals are routinely used in fracking and that flowback fluids mobilise toxic and radioactive materials. It is admitted that there is a risk that even if contaminated surface water does not directly impact drinking water supplies, it can affect human health indirectly through consumption of contaminated wildlife, livestock, or agricultural products and that leakage of waste fluids from the drilling and fracking processes has resulted in environmental damage

- a) Water

Impacts on water quality and quantity are the most highly publicised environmental effects associated with shale gas fracking, with potential human health consequences for local rural communities. Hydraulic fracking increases the amount of fresh water used by each shale gas well by as much as 100 times the quantity used in conventional drilling. The IOD estimate that water use for shale gas could reach 5.4 million m3 a year, around 0.05% of the total. This would equate to 27,000 four people households using 200 m3 of water per year. It is also a similar amount of water that is currently being used on existing mining/quarrying operations which is estimated by WRAP4 at 7 million m3 a year.

In the US the chemicals that are added to the water have raised public health concerns related to surface water and groundwater quality. Although chemical additives used in fracturing fluids typically make up less than 2 percent by weight of the total fluid they do include biocides, surfactants, viscosity modifiers, and emulsifiers which vary in toxicity.

A proportion of the fluids used in drilling returns to the surface; these “flowback” or “produced” fluids may contain hydraulic fracturing chemicals, as well as heavy metals, salts, and naturally occurring radioactive material from below ground. This water must be treated, recycled, or disposed of safely otherwise surface water may be contaminated by leaking on-site storage ponds, surface runoff, spills, or flood events. There is a risk that even if contaminated surface water does not directly impact drinking water supplies, it can affect human health indirectly through consumption of contaminated wildlife, livestock, or agricultural products.

Experience from the US indicates that leakage of waste fluids from the drilling and fracking processes has resulted in environmental damage. Although it is unlikely that contamination will occur via the artificially created fractures in the rock, leaks can potentially occur through faulty well construction or from surface spillage of drilling and fracking related fluids (IEA, 2012; The Royal Society, 2012). Royal Society5 research shows that the majority of incidents of contamination in the US occurred under historically weaker environmental standards than are currently adhered to and that the UK regulatory environment is likely to be more robust. For instance, waste fluids will need to be stored in sealed steel tanks rather than open ponds, which reduce the risk of leakage.

The Environmental Impact Assessment commissioned by DECC identified that the additional volume of waste water could place a significant burden on existing treatment infrastructure capacity, and require further or new investment. Overall the potential impacts on water resource availability, aquatic habitats and ecosystems and water quality is uncertain. Water would typically be sourced from a mains water supply which would need agreement from the relevant water company, or could be abstracted from groundwater or surface water which would need an abstraction licence; in either case, any addition to demand would only be granted where assessed by the regulator as sustainable. Demand could however be substantially reduced if it could be met from recycling and reuse of flow back water.

Again here we see a clear indication that it is likely that flow back water will be reused giving the lie to the oft-repeated claim that no toxic material will be injected.

Now we see that the assessments of Noise and Light impacts were also considered to sensitive for us to be allowed to see them – possibly because a clear link to health impacts is admitted. Strangely this section also includes the admission that fracking does cause seismic activity.

-

b) Noise and Light

Noise and light have also been cited in the US as environmental and health concerns for residents and animals living near drilling operations. Excessive and/or continuous noise, such as that typically experienced near drilling sites, has documented health impacts. According to community reports near these sites, some residents may experience deafening noise; light pollution that affects sleeping patterns. Noxious odours from venting gases can also impact on air quality for local residents.

NYSDEC (2011) reports that noise impacts can be felt close to distance to the extraction site. There is also the potential for hydraulic fracturing to cause earthquakes and seismic activity. According to de Pater and Baisch (2011) and Green et al. (2012), hydraulic fracturing can cause noticeable seismic activity. Also, pressure in disposal wells can build up over time, inducing seismicity (The Royal Society, 2012). These risks would need to be properly regulated and managed to minimise the impacts.

Now we get onto landscape and we can see that DEFRA wanted to hide the conclusion that fracking will indeed industrialise a previously rural area and that this will have clear negative impacts on local industries and amenity value

- c) Landscape

Environmental impacts on the landscape are another consideration. Shale gas development may transform a previously pristine and quiet natural region, bringing increased industrialization. As a result rural community businesses that rely on clean air, land, water, and/or a tranquil environment may suffer losses from this change such as agriculture, tourism, organic farming, hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation.

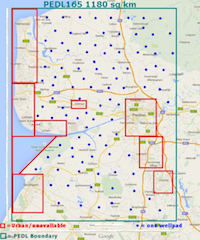

The map in the diagram below illustrates the potential impact of the Bowland shale gas exploration area which cuts across a number of National Parks and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, including the entire Peak District National Park. However, the size of the extraction pads will be small relative to the potential area. Various sources give estimates of the land area taken up by an extraction pad, which may include multiple wells. The IEA (2012) estimate a typical size of one hectare, while Tyndall Centre (2011) estimates a size of between 0.4 and 2 hectares. The largest estimate is from Cooley and Donnelly (2012) at 3 hectares. MacKay and Stone (2013) estimate the potential size of a pad in the UK, at 0.7 hectares. The SEA report assumes each well pad will cover 2 to 3 hectares. The Ricardo AEA report gives a range of areas, based on US experience from 2 to 3.6 hectares.

The SEA report suggests the total area covered by well pads will be between 60-90 hectares (low scenario) and 240-360 hectares (high scenario). It assumes 6-12 wells per pad (low scenario) and 12-24 wells per pad (high scenario). The Ricardo-AEA scenarios produce a total land take of 200 hectares (low growth), 1080 hectares (medium growth) and 4400 hectares (high ‘US style’ growth). These figures are based on land requirements for well pad development, drilling hydraulic fracturing and completion stages only. During the operational phase the landtake would be lower. Overall the results suggest that the landscape impacts will be relatively low in comparison to other extractive industries such as quarrying.

The redacted section on waste is quite anodyne given the problems they actually face in disposing of radioactive fracking fluid, but it could hardly be left in on its own

- d) Waste

A typical fracking site will produce waste liquids from both drilling the well and the fracking process itself (IEA, 2012). Treatment of some waste fluids may produce solids that would typically be disposed of via landfill (The Royal Society, 2012). Any products sent to landfill would attract the landfill tax and, as such, the impact will be incorporated into the calculation of operational costs already. No other evidence was identified to support any suggestion that this impact could be significant.

The redactions on air quality contain an admission that VOCs can be deleterious to health.

- e) Air Quality

Some studies have found evidence of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), such as benzene, near shale gas extraction sites in the US, particularly during uncontrolled flowback of fracking fluid (McKenzie et. al., 2012; Colborn et. al., 2011). VOCs contribute to ozone and smog formation and can result in adverse health effects. However, the literature is limited and uncontrolled flowback and open storage of fracking fluids on site would not materialise in the UK due to the regulatory regime in place (The Royal Society, 2012).The combustion of natural gas produces a number of air pollutants, including particulate matter (PM), oxides of nitrogen (NOx), sulphur dioxide (SO2) and ammonia (NH3). However, levels of pollutants released from shale gas production are relatively low, and when valued represent a negligible cost.

Obviously the summary table dealing with the points above was redacted too

Table 3: Summary of environmental impact of shale gas on rural communities

| Water resources | Noise | Air Quality | Landscape |

| Low impact if properly regulated but risks need to be managed effectively on site. | Localised impact on rural communities living within close proximity of shale gas fracking operations | Low impact If properly regulated but risks need to be managed effectively | Low impact that is site specific, although will have localised impact on businesses reliant on tranquil environment |

Within Section 4 – Conclusions we lost

Overall the impacts are likely to be mixed with short-term positive economic gains from employment and energy that need to be balanced against the costs that may affect certain groups, such as businesses involved in tourism, local house price impacts and increased congestion.

It is not hard to see why that paragraph disappeared is it?

A paragraph on localising any benefits got the blue pencil

This report has not considered whether existing regulations for these activities will be sufficient to cover the expansion of shale gas and limit the impacts for rural communities. These issues are expected to be covered in the other regulatory reviews that have been commissioned.

However, there may be some important lessons to be learnt from experiences of these other extraction sectors. For example, a report from the quarrying industry6 suggested that a way of further localising the positive economic benefits is to foster the development of the vertical and horizontal economic linkages between the proposed quarry and the existing community. This can be facilitated, for example, by encouraging prospective quarry operators to adopt a policy of favouring the procurement of materials, equipment and services from local suppliers and distributors or giving better rates to local buyers. In addition, the economic and social development of a local area affected by quarrying activities has sometimes been enhanced through seed funding donated by the operator, which is administered by the local authority, but made available to the community for projects.

HMT also introduced an aggregates levy7 in 2002 that was aimed at reducing the environmental externality costs associated with quarrying aggregate material. Part of the revenue was used to reduce National Insurance contributions to promote employment and some was used in a Sustainability Fund for local projects.

Next we lose a paragraph touching on the transience of the industry and the boom and bust it may bring with it.

Although many rural communities may therefore gain in the short-term from the expansion of shale gas activity it is also important to consider the longer-term effect as companies exit the market. This will have implications for the potential benefits, costs, job creation and longer term economic development prospects for rural communities where shale gas drilling is taking place.

and finally we lose ALL of the recommendations. All of these are to an extent hostages to fortune so we are not surprised that these were suppressed. However it will now be very hard for government to back away from these as at least minimum requirements

Section 5: Recommendations

Some specific recommendations from the Royal Society report that are relevant in the context of protecting rural communities from the impact of shale gas expansion include:

- An Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) should be mandatory for all shale gas operations. Risks should be assessed across the entire lifecycle of shale gas extraction, including risks associated with the disposal of wastes and abandonment of wells. Seismic risks should also feature as part of the ERA.

- Water requirements can be managed through integrated operational practices, such as recycling and reusing wastewaters where possible. Options for disposing of wastes should be planned from the outset.

iii. Shale gas extraction in the UK is presently at a very small scale, involving only exploratory activities. Uncertainties can be addressed through robust monitoring systems. There is greater uncertainty about the scale of production activities should a future shale gas industry develop nationwide. Attention must be paid to the way in which risks scale up. Co- ordination of the numerous bodies with regulatory responsibilities for shale gas extraction must be maintained. Regulatory capacity may need to be increased.

- Risk assessments should be submitted to the regulators for scrutiny and then enforced through monitoring activities and inspections. It is mandatory for operators to report well failures, as well as other accidents and incidents to the UK’s regulators. Mechanisms should be put in place so that reports can also be shared between operators to promote best practices across the industry.

Other recommendations could also include:

- Ensuring that adequate provision of local infrastructure and maintenance are included within the plans for expanding shale gas drilling operations. This would ensure that roads are protected from the impact of heavy vehicles and water infrastructure has the capacity to deal with increased demand.

- Encouraging operators to offer employment and training opportunities to residents living in rural communities both direct and indirect via supply chain contracts so that they benefit from the increase in economic activity.

vii. Planning for the longer-term when operations are scaled back and site mediation to ensure that tourism and other local business activities have opportunities to benefit.

viii. Routine monitoring and evaluation of the impacts of shale gas drilling to ensure that negative externalities (noise, congestion, air quality etc) are kept within acceptable limits.

It is also clear from these recommendations that there are HUGE uncertainties about how shale gas could or should develop in the UK.

Overall it sees that these redactions were not strictly necessary as the whole report is basically a cuttings job pulling together other reports. What is perhaps damning though is the fact that even the limited conclusions reached here were considered so toxic that they took the foolish risk of suppressing them using redaction. This arrogance has returned to haunt them now with a vengeance . Geoffrey Lean writing in the Telegraph this week said

While the industry continues to show such complacency over fast-vanishing public support – and such contempt for local people – it will go on losing, and badly.

We need to add the government to that statement as well.

For Friends of The Earth’s reading of the redactions visit their blog where Tony Bosworth has written his thoughts