So what would 100 40 well pads look like (numerically)

- 4000 wells would require 100 well pads even if they could manage 40 wells per pad

- 4000 wells would only generate about 12.5 TCF of gas using IoD estimates for EURs

- It would take nearly a decade to produce 1 year’s worth of UK gas demand

- It would require nearly 2/3 of Europe’s existing drilling rig count to be in use at any one time for 12 years

- It would only produce 0.3 TCF of gas a year on average over the 40 years required to drain the wells.

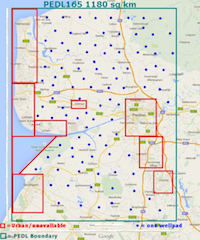

A short while ago Alan Tootill did some analysis of the number of wells that might be required to service Cuadrilla’s project in Lancashire. Alan took the much quoted scenario of one hundred well pads, with forty wells per pad, used by, amongst others the Institute of Directors (IoD). Alan was concerned there with well spacing and land take but I want to concentrate on productivity here and in particular the phasing of the productivity, and how that means that the gas produced from 4,000 wells would in no way justify their creation and would call into question the role of the gas as a meaningful contribution to energy security or to acting as a transition fuel.

Let’s take a look shall we?

One of the most critical factors is the EUR of the well. EUR is the “Estimated Ultimate Recovery” per well and is normally expressed in BCF (billion cubic feet) of gas. Forecasting EUR’s is a complex job and the answers vary according to several factors including the initial productivity of the wells. There is normally a fairly wide range of EURs across a field as some areas (the “sweet spots”) are more “prospective” for gas than others. There is an interesting paper on it here . Whilst the only thing we know about any forecast is that is likely to be wrong, we have to make certain assumptions about EUR to be able to model likely impacts. The IoD report “Getting Shale Gas Working” was based on projected EURs per well of about 3.2 BCF, so we’ll be kind and use that figure here. There is much evidence from the existing plays in the USA to suggest that that figure may be optimistic.

The next factor is the production decline curve. Productivity of fracking wells declines sharply in the first few years, although it can be increased by re-fracking. Whether re-fracking is commercially viable is a simple equation between the cost of re-fracking and the future value of the extra gas that might be extracted. Recent research suggests that the productivity decline is hyperbolic for a time before becoming exponential.

I have used here a “Modified Hyperbolic Decline curve” to model the annual productivity of a 3.2 BCF EUR well over a 30 year productive life.

Finally we have the production schedule – I have used the 12 year production schedule for 100 x 40 well pads suggested by the IoD here. It shows a ramping up of pad development over 4 years before reaching a constant 10 a year.

Putting all of this together we can model the annual productivity of the PEDL 165 project.

This is based on the IoD drilling schedule, an average EUR of 3.1 BCF per well and the same modified hyberbolic decline curve for each well. You can perhaps see why fracking is such a capital intensive business as without new wells being drilled productivity drops off dramatically after year 12 with the last 30 years generating just 7.2 TCF of gas compared to 5.25 in the first 12. By way of comparison, over recent years, UK consumption of gas has averaged about 3 TCF a year, although a decline in usage in the last year or so allows DECC to suggest it is now about 2.5 TCF a year, which helps them make their case as they can claim more years of supply.

This shows us first of all that productivity climbs as more wells are drilled over 12 years (an average of 333 wells a year), but then falls off steeply as wells stop being drilled after year 12.

333 wells a year is 28 a month.

Now given that according to http://www.shalereporter.com it takes 1-2 months to set up a pad and then about a month to drill each well,

“The final pre-drilling action is to stake the well and plan out the well pad boundaries which takes one to two months. The next step is the drilling and completion stage, which begins with drilling the well to the required depth, this can take a month or so.”

it might be reasonable to ask how this number of wells might be drilled, when according to the service company, Baker Hughes, (quoted in “Exploration in Europe: Trends and Challenges” by the International Association of Oil and Gas producers) “Europe currently has 50 onshore rigs active in 12 countries with a median count of 2 per active country In Europe”.

It looks as though we are going to need almost 2/3 of Europe’s existing rig count in PEDL 165 on a constant basis for 12 years if and when they start drilling.

However, lets’ not get bogged down by practicality – let’s assume that they can magic up these drilling rigs from somewhere and drill 333 wells a year somehow…

What is equally interesting is the way in which cumulative productivity is phased

You will notice that it takes 9 years from the start of production before enough gas to service 1 years UK consumption has been extracted, so we are probably 15 years away from being able to say that PEDL 165 and it’s hypothetical 4000 wells would have generated a single year’s supply of gas.

For 12 of those years we would need more than half the rigs that currently exist in Europe drilling constantly and their associated pads being serviced with constant deliveries and removal of fluids, fracking sand and chemicals. Apart from in urban areas (and maybe not even there) it is unlikely that anyone in the area will find themselves living more that 2 miles away from a fracking pad.

Over a 41 year productive lifetime it might generate 12.5 tcf – an average of 0.3 TCF a year and a total of 4 or 5 years of UK consumption depending on whose consumption figures you choose to use.

Now, is it really worth drilling 4,000 wells in the rural Fylde for this?